On December 16, 1944, the Germans launched a massive attack against the Allies in the Ardennes that became known as the Battle of the Bulge. Some 250,000 German troops in 14 infantry divisions along with 5 panzer divisions surged forward against just 80,000 American troops defending a 60 mile front.

Of the roughly 180,000 US deaths in World War II in Europe, nearly 40,000 of them are tied to this battle. The US would suffer the 2nd largest surrender of troops of the war as some 7500 troops of the 106th Infantry Division surrendered at one time at Schnee Eifel (12,000 Americans surrendered at Bataan in the Philippines in April of 1942). The fighting was so intense that desertion became an issue. So much so that General Eisenhower felt forced to make an example of Private Eddie Slovak, the first and only American executed for desertion since the Civil War. More than 21,000 Americans received a military sentence of one kind or another for desertion including 29 death sentences. All were commuted except Slovak’s who had the misfortune to be undergoing a clemency review just as the Battle of the Bulge was raging and at a time when Army moral was at a low point due to fighting losses. The personnel situation was so bad that cooks and truck drivers were handed weapons and sent to the front lines.

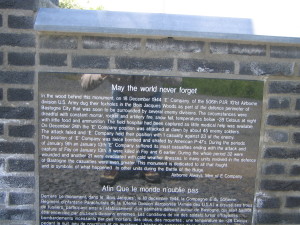

During the course of the battle, the Nazis would commit a number of atrocities including the murder of 72 captured US troops at a place called Malmedy. And at another place called Wereth, a tiny hamlet in Belgium, 11 black troops of the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion were murdered by the SS.

It all began with a desperate plan by Hitler to try to split the allied armies and recapture the only functioning deep water port of Antwerp that was available to the allies in 1944. The hope was to isolate and cutoff the British and Canadian Armies north of the surging German Army and to force their surrender. If Hitler could not force the British and Canadian Armies to surrender, he hoped to at least try to split the Allied resolve for unconditional surrender. If Hitler could somehow accomplish this, maybe he could survive the war and remain in charge in Berlin. At a minimum, by reaching Antwerp, the Germans hoped to cut off the easy flow of supplies to all the Allied Armies in Europe and force them to go back to landing supplies in Normandy which meant huge logistic issues. Their hope was to slow down the assaults from the west so that Germany could put more of its shrinking resources into fighting the Russians who were moving west through Poland towards Berlin.

The allies were not totally in the dark about a coming German offensive. Despite the Germans trying to keep radio traffic to a minimum, decoded “Ultra” intercepts from Bletchley Park indicated that the Germans were massing for an attack although the date was uncertain. The real culprit here was the total belief by Eisenhower’s staff that the Germans were all but beaten. General Omar Bradley, in charge of the US 1st Army in the Ardennes was completely caught off guard and was lucky that he was not relieved of duty and sent home. As was often typical of the fighting in World War II, the German Generals, in this case Walter Model head of Army Group B and Gerd von Rundstedt completely outmaneuvered their American counterparts in the initial stages of the battle . And as was also typical of the Allied Generals of World War II, only one US General, George Patton, was able to act decisively and effectively to counter the surging German Army with a decisive attack of his own.

Leading the charge west for the Germans were 2 Panzer Armies. At the front of the attack was Joachim Peiper of the 6th Panzer Army who was one of Germany’s most decorated tank commanders. It was Peiper’s SS division that would perpetrate the Malmedy massacre on December 17 on the north side of the bulge. He and the overall commander of the 6th Panzer Army, Sepp Dietrich would be put on trial for their involvement in the massacre after the war.

South of Dietrich’s 6th Panzer Army, von Mantueffel’s Fifth Panzer Army attacked towards Bastogne and St. Vith, both road junctions of great importance with many roads leading out of them in all directions. Capturing these towns would give the Germans many options of where to attack next, making it more and more difficult for the Allies to defend and stop the assault.

As the battle raged, the Germans were able to surround Bastogne but could not capture it due to the tenacious defense by the US 101st Airborne. Additionally, the Germans failed to capture the high ground of the Eisenborn Ridge. Elements of the 99th Division of the US 1st Army Group under Hodges were able to hang on to the dominating heights of the ridge with effective help from the British XXXth Corps artillery. If Peiper had pushed the Americans off the Eisenborn Ridge, he could advance on the River Meuse. And if he could cross the river, the path to Antwerp was wide open.

Despite launching a surprise attack with overwhelming force, the Germans had plenty of their own problems. Their first was that Hitler promised the Wehrmacht nearly 50% more tanks than what was actually delivered. Despite having a fresh supply of Germany’s largest King Tiger Tanks, a 70 ton beast firing an 88 mm cannon that could cut through the armor of a US Sherman Tank like a hot knife through butter, they only had about 100 of them. These were mixed in with tanks of other designs. Additionally, the Germans suffered from a severe lack of fuel and the advancing Panzer Armies were forced to forage for fuel as they tried to attack west.

An even bigger German problem was that the Luftwaffe was mostly out the picture by December of 1944. As a result, the Germans had little ability to attack from the air or even to get aerial reconnaissance of the Allied positions. Coupled with the bad weather that kept everyone’s planes from flying, this severe limitation kept the Germans from knowing exactly where along the Allied lines they should attack to achieve the best results.

Further confounding the German effort was the ability by the Allies to eventually muster a huge force to counter their attack. The British under Montgomery began to arrive with large amounts of artillery and began pounding the advancing units of the 5th Panzer Army along the northern edge of the bulge on December 22. On the southern edge of the bulge, Patton’s 3rd US Army began arriving on December 23 and started cutting into the German’s southern flank. Patton was heading towards Bastogne where he intended to relieve the besieged 101st Airborne.

By December 24, with the weather starting to clear and more Allied divisions entering the fight, the German position was becoming more and more untenable. Allied resupply by air began on December 23 and large numbers of American P-47 Thunderbolt fighters began cutting into the advancing Panzer units.

On December 26, the lead elements of Patton’s army broke through to Bastogne which effectively left the advancing German armies with no easy means of retreat.

The Wehrmacht knew their position was becoming precarious on December 24 when they failed to capture the bridges over the Meuse. That evening General Hasso von Manteuffel recommended that Germany halt all forward efforts and withdraw. Hitler rejected the idea and the Germans fought on.

Heavy fighting continued for some time despite the ever worsening position of the Germans and the strengthening of the Allied position. On January 1, Eisenhower pressed General Montgomery for all out British attack from the north and for Patton to continue his drive north into the southern flank of the Germans.

As with what happened in Normandy at Falaise, for a number of reasons, the Allies were not able to close the gap and trap all the Germans inside the pocket. Large numbers of Germans would eventually escape back into Germany from the bulge after January 7, when Hitler finally agreed to allow their retreat. Even with this, it took until nearly the end of January for the front line to return to where it was before the attack began.

Although the battle is often thought of as mostly an American victory, the truth is a bit more complicated and a lot more interesting. General Omar Bradley’s handling of the US 1st Army was so poor during the battle that several of his largest divisions were moved under British General Montgomery’s command. Montgomery was able to reorganize the chaos and bring his artillery units into action against the Germans. But Montgomery and the US Army held each other in tremendously poor regard. Montgomery, often prone to self aggrandizement, held a press conference on the same day that Hitler ordered a withdrawal (January 7) where he described his own contribution as being the most significant part of the allied victory despite US troops outnumbering British troops by 10:1. As you could expect, the reaction of the US commanders was not good. Both Patton and Bradley threatened to resign. Eisenhower, encouraged by his British deputy, Arthur Tedder, who also disliked Montgomery, decided to fire Montgomery for even holding the press conference in the first place. It was only due to the intervention of Eisenhower’s Chief of Staff, that Eisenhower reconsidered and allowed Montgomery to just apologize for his poorly timed comments. All this controversy created by Montgomery probably saved Omar Bradley from being fired for his lack of defensive preparation in the first place. Either way, it all once again proved that if something big needed doing, Patton was the General who could get it done.

More than 600,000 US soldiers fought in the Battle of the Bulge and it was the deadliest of the US battles of WW2 with more than 80,000 casualties.

For black soldiers in the US Army, the battle proved to be a turning point in the history of the US Army. The shortage of fighting men forced the army to integrate many of the units fighting in the battle by bringing in black soldiers to fill in for battle loses. By breaking down this barrier to integration during a time of crisis, the US Army was no longer able to justify the segregation policy under which it had previously operated. This opened the door to full integration of the armed forces by President Truman a few years later.

Up until this point of the war, black soldiers were often relegated to all-black support units such as cooks and truck drivers. During the fighting in Italy, several all-black infantry units under US General Marc Clark had abandoned their positions during heavy fighting. Clark had written scathing reports to the General Marshall about the behavior of these all-black units. This reinforced all the stereotypes that the US Army had used to justify the non-integration policy. There is no equivalent story to the Tuskegee Airmen in the US Army’s history. But the positive result of integrated units with black soldiers fighting during the Battle of the Bulge completely changed the situation.

At the end of the battle, Germany had suffered over 85,000 casualties and had used up most of Wehrmacht’s personnel reserves. The Luftwaffe was further decimated and the Allies were poised to enter Germany proper as they raced toward the Rhein. Hitler’s hope of some sort of separate negotiated peace with the western allies was dashed thus ending any chance he might have thought he had to survive the war.